On May 25th, 1979, the United States suffered its deadliest single-aircraft accident. American Airlines Flight 191, a McDonnell-Douglas DC-10, was taking off from Chicago-O’Hare International Airport runway 32. At rotation the number one engine, pylon, and three feet of the wing leading edge separated from the aircraft and landed on the runway.

Losing an engine isn’t automatically catastrophic; aircraft are designed to be capable of continued flight after losing thrust from one engine. But seconds later, Flight 191 rolled sharply to the left and crashed into a nearby hangar, killing all 271 people on board and two on the ground. A horrific event – but not an accident. This was unfortunately a predictable outcome.

The pilots were immediately criticized considering that the loss of one engine should not have caused a crash. The media of the day was quick to blame the aircrew and, unfortunately, this tendency continues today. It’s always easy to blame dead pilots. But the flight crew of American Airlines Flight 191 was very experienced. Captain Walter H. Lux had logged 22,000 flying hours, 3,000 of those on a DC-10. First Officer James Dillard and Flight Engineer Alfred Udovich were also highly experienced. What the media failed to consider was that the engine had not just failed, it separated from the airplane. This caused significant damage to the wing and leading-edge slats. The asymmetric stall that resulted was unrecoverable.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) quickly zeroed in on maintenance records. They were traced to an American Airlines facility conducting work on that engine a short time before the crash. The details of the procedure used became the root cause of this terrible crash.

To save time, the workers had modified a key procedure that had become common industry-wide, unbeknownst to McDonnell-Douglass. The maintenance team was supposed to carefully remove the engine from its support pylon, requiring the removal of hundreds of connectors in the process. Instead, they cut corners and removed the engine and pylon together. This method required the removal of only three bolts. This saved significant time but was not the proper procedure.

To reinstall the engine, workers used a forklift to lift it back into place. A forklift is difficult to control with the preciseness required for this operation. Its use resulted in so much pressure that a crack was created. From that point on, each time the plane took off, the crack grew larger. It was only a matter of time before it failed. In the final NTSB investigation report it was determined that “the separation resulted from damage by improper maintenance procedures which led to failure of the pylon structure.”

The investigation also revealed that when the engine detached, it struck the wing with enough force to rupture hydraulic lines, causing significant loss of hydraulic fluid. Without that fluid, the remaining slats retracted sending the plane into an asymmetrical stall. Additionally, because of the loss of the engine driven generator the stall warning system was disabled including the stick shaker. The pilots had quickly transitioned to the safe engine-out climb speed (V2) as would be appropriate for the loss of the left engine thrust. Unfortunately, at that speed the left wing stalled due to the damage and the uncommanded slat retraction.

Eventually, the NTSB determined that the aircrew acted appropriately based on the information they had. Additionally, the FAA issued a series of air worthiness directives aimed at filling the gaps this tragedy had exposed. These new directives required updates to aircraft electrical systems to prevent total stall-warning failure, along with stricter maintenance protocols and other safety improvements.

The 273 lives lost that day cannot be brought back, but we can stop others from being lost. We must understand that these tragedies are not isolated accidents, they are the final link in a long chain of preventable errors. Blaming the pilots only distracts from fixing what truly went wrong.

This crash happened in 1979; but this pattern of initially blaming pilots is still happening today. However, pilots have little control over what happens before they step into the cockpit – they have limited visibility in how an aircraft is designed, maintained, or repaired. This blame game was not new in 1979, and it continues to happen in today’s media circus. Look no further than the Air India 171 crash. An incomplete and potentially misleading initial investigation report implies pilot actions caused this crash without a thorough examination of all the evidence. History repeats itself once again?

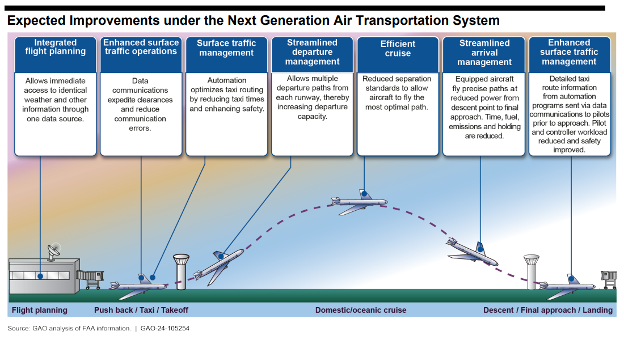

In 2003, the FAA launched a new program intended to revolutionize the air traffic control system in the U.S. The Next Generation Air Transport System (NextGen) was designed to make the system safer and more efficient by introducing new technologies. However, as was detailed in the May edition of the Aviation Watchdog Report, this initiative has failed to deliver on its promises. The U.S. ATC system has fallen behind most of the developed world as equipment is antiquated and air traffic controller staffing shortages continue to wreak havoc across the country.

On September 29, 2025, the Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued a Capstone Memorandum detailing the NextGen successes and failures. According to the OIG, NextGen delivered only 16% of the expected improvements despite 22 years of effort and a cost of $36 billion. FAA has struggled to manage cost overruns, integrate new systems, and made exceedingly optimistic estimates. Delays were also increased due to the pandemic impact on transportation and logistics. The OIG further stated that they have made over 50 reports and 200 recommendations since 2006. In a November 2023 report to Congressional Committees the OIG stated, “Since 2018, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) made mixed progress meeting milestones in its ongoing effort to modernize air traffic management, known as the Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen).”

DOT Secretary Duffy has now proposed the development of a completely new air traffic control system. Duffy has warned that, “people will lose their lives” if the system is not improved. These improvements are vital to aviation safety, but also important for national security and the economy. The Foundation is hopeful that this initiative, with its estimated cost at over $30 billion, actually reaches the stated goals within a reasonable timeline. Unfortunately, we’ve been down this road before with NextGen. We simply cannot afford another federal government failure.

As the investigation into the June 12, 2025, crash of Air India 171 continues so does the controversy surrounding it. After a weak, incomplete, and seemingly misleading initial investigation was released the news from India continues to disappoint because of an almost total lack of detailed information. Many groups, from labor unions to victim family members, continue to raise concerns about the AAIB’s handling of the crash investigation and the safety of the Boeing 787.

It is understood that a preliminary report is just that. Many details are unknown when issued and analysis or interpretation of data is inappropriate. However, there are a multitude of details missing that should have been included or at least commented upon. These include a clear timeline of all significant events including engine start times and checklist completions. Complete FDR information, and CVR transcripts could have been included. Additionally, the 787 is equipped with an Airplane Health Monitoring system (AHM) that should have been transmitting performance and maintenance data in real time. There is no mention of this in the report.

Meanwhile, on October 4, 2025, Air India Flight 117 from Amritsar to Birmingham, England, experienced a ram air turbine (RAT) deployment just prior to landing. The Federation of Indian Pilots has demanded a full investigation. Charanvir Singh Randhawa, president of the pilots’ union, said, “It’s a serious concern that warrants a detailed inquiry.”

Then on October 9, 2025, Air India flight 154 experienced autopilot and additional system failures during a flight from Vienna to Delhi. The flight diverted to Dubai before continuing on to Delhi after several hours on the ground. An Air India spokesperson said in a statement to The New Indian Express that the aircraft was diverted due to a "technical issue."

India’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) has directed Air India to reinspect the RAT systems on all Boeing 787 aircraft with recently replaced power conditioning modules. The DGCA has also requested a report from Boeing detailing preventive measures and any available data on similar RAT deployments around the world.

All of this is happening as the AAIB remains silent regarding the Air India 171 investigation progress. Families of four crash victims have filed suit against Boeing and Honeywell alleging that by installing the fuel cutoff switches behind the thrust levers, “Boeing effectively guaranteed that normal cockpit activity could result in inadvertent fuel cut-off” and that the switches had defective mechanisms that made unintentional switch movement possible. The FAA had issued recommendations to inspect installed switches on Boeing aircraft in 2018, but those inspections were not mandatory, and Air India did not complete them.

The father of Captain Sumeet Sabharwal, flight 171’s captain, has also added more pressure to the AAIB by demanding a new independent investigation as he feels the preliminary report unjustly defamed his son by implying that he moved the switches to fuel cutoff intentionally.

These are just some of the problems that result from poor, absent, or misleading communication between investigators and members of the public. It’s been over four months since Air India flight 171 crashed in Ahmedabad, killing 260 people including 19 on the ground. With little official information the aviation community is left to speculate or attempt separate investigations through research and leaked documents from anonymous sources that may or may not be authentic. This is also heartbreaking for victim family members as they see public concern diminish. In the meantime, the 787 continues to fly around the world as we all hold our breath hoping that another disaster does not occur.

The Foundation for Aviation Safety calls for a new Aviation Accident Investigation Process that emphasizes transparency, collaboration, and independent analysis, enabling global experts to contribute in near real-time.

You can see our recent news release here.

International accident investigations—structured under ICAO Annex 13—were designed in the 1940s. They no longer reflect the realities of modern aviation. Complex aircraft, multinational supply chains, and powerful corporate actors have overcome outdated procedures, leaving investigations vulnerable to conflicts of interest, political interference, and bias.

The basic structure includes inherent limitations and conflicts of interest. The “state of occurrence” clause entraps the investigation within a locale that could include governmental influence and bias. The outdated investigation protocol is often limited to mechanical failures or pilot error when software, automation, scheduled maintenance, supply chain integrity, manufacturing or design flaws, or cybersecurity are more applicable causal factors in today’s aviation industry.

Including aircraft manufacturers as “technical advisors” or “accredited parties” to an investigation is especially problematic. In a perfect world these experts would offer insight and system knowledge that could quickly lead to pertinent causal factors. Unfortunately, in today’s environment those experts can easily be motivated or pressured into deflecting any culpability. This conflict of interest is obvious and manifests itself in the tendency to immediately blame the pilots for any accident before all evidence has been analyzed and all potential causes are fully investigated. The Air India 171 accident is a prime example. An incomplete and intentionally misleading initial investigation report is clearly intended to place blame on the pilots when no such conclusion is appropriate in initial investigations and could not have been made based on the available evidence.

The process is additionally complicated by the pace of investigations. Accident investigations are undertaken for one reason- to prevent a recurrence. When investigations take well over a year, sometimes even much longer than that, the safety lessons to be learned may come too late. This extended timeline only serves to diffuse the public outrage and lessen the impact on the eventual responsible parties. These are understandably complex undertakings but with the modern technology available today it is inconceivable that investigations should take so long to complete.

The investigation reform must strive to transform the process into a globally collaborative, transparent, and expert-driven process that accelerates safety improvements worldwide. The lead investigative body must follow a strict timeline and transparency protocol. This should include mandated public hearings and press conferences early and often. The lack of transparency we see today serves only those who have something to hide. The flying public has a right to know all the details of any crash investigation. After all, they are the people who put their faith in the aviation system and are the ones who pay the ultimate price for its failure.

Current investigative bodies are understaffed and far too reliant on aircraft manufacturers to supply technical support. This model often puts the fox in the henhouse as aircraft malfunctions, design shortcomings, or manufacturing defects often play a major role in modern day aviation accidents. These entities are far too cozy with industry and susceptible to government influence. As we’ve reported many times, the NTSB is currently withholding documents related to the ET-302 crash despite the Ethiopians’ request for this information. There is no safety related justification for this; it can only be political or financial. There is no place for this in aviation safety.

A new system that engages unbiased technical experts, determines probable causes in a timely manner, and releases all pertinent information to the public should be the fundamental structure of a new investigation process. This is vital to preserving the integrity of accident investigations and the safety of the flying public worldwide.

The Foundation calls for a worldwide effort to revamp the investigative process. In today’s world of instant communication and advanced investigation techniques there is no justification for continuing to rely on decades-old processes and procedures that are subject to bias, industry influence, insufficient budgets, or political motivations. Aviation safety is too important to everyone.